yikes/bye

on leaving Substack, missing the Toast, and being disappointed by companies

Hey, y’all.

You may remember that a few weeks ago, I talked about the disturbing state of things at Substack, the platform that hosts this newsletter. And then I sort of followed up about it, and then I didn’t mention it again. That’s because I didn’t want to make a decision about this newsletter while the situation was developing, and I didn’t have time to analyze the facts anyway, because I have a real job again. It’s been really difficult for me to balance the newsletter with work lately, and I want to make sure that I’m being responsible in sharing information — for example, after the Atlanta shootings. There are only so many hours a week I can devote to working on Friendmendations, and I haven’t had time to read about and reflect on what was actually happening with Substack or look into my options.

The tl;dr announcement here is that I’ll be moving Friendmendations from Substack to Ghost, which shouldn’t impact your reading experience. Ghost and Substack both process payments through Stripe, so paying subscribers won’t see their payments interrupted or anything, and the newsletter will continue to go to your inboxes as per usual. Things will be messy on my end for a while, as I sort out all the links that will end up broken, but that shouldn’t impact y’all. I think the next few posts will go out on Substack as I migrate over, but I’ll let you know when it’s been fully transferred to Ghost, in case anyone habitually reads in their browser.

So, hey, let’s talk about why I’m doing this!

My last post on the topic is a good primer on the situation and my feelings about it. Many writers have since announced their departure from the platform. Of them, I found Nathan Tankus’s explanation the most clear and thorough, and I highly recommend reading it. This excerpt in particular sums up the situation well:

Major journalists and opinion writers with pre-existing platforms began to leave large publications with editorial oversight for Substack. They largely or fully attributed their departures to “illiberalism” or persecution because of their “ideology.” Their immediate Substack output tended to revolve around the supposed excesses of “woke culture” and “cancel culture.” These writers seem to treat obscure internet controversies as far more important than the actual life-threatening crises we’ve been experiencing for the past year. It began to be embarrassing to be associated with “Substack,” when this is the reputation they’ve been taking on.

While annoying, I wasn’t particularly concerned about these developments because I thought that this was an open platform with plenty of writers I disagreed with. However, it’s become clear that Substack is specifically seeking out these big named writers. In some cases they’ve paid them large six figure advances to move to Substack. It doesn’t take much effort or intellect to spend your time denouncing movements for justice, and now there is big money to be made doing it.

His post discusses the egregious behavior by Graham Linehan in particular, the one Substack writer who seems to be the most clearly violating Substack’s stated rules banning harassment, doxxing and hate. (Most egregiously, Linehan recently created a profile on a lesbian dating app to take screenshots of trans women, then shared them in a public post for his newsletter without obscuring their identities.) In her newly launched newsletter as a Substack Pro writer, Grace Lavery details the case against Linehan and how his behavior differs from that of the less overtly harmful transphobes on the platform, urging Substack to uphold their own rules and ban him from publishing.

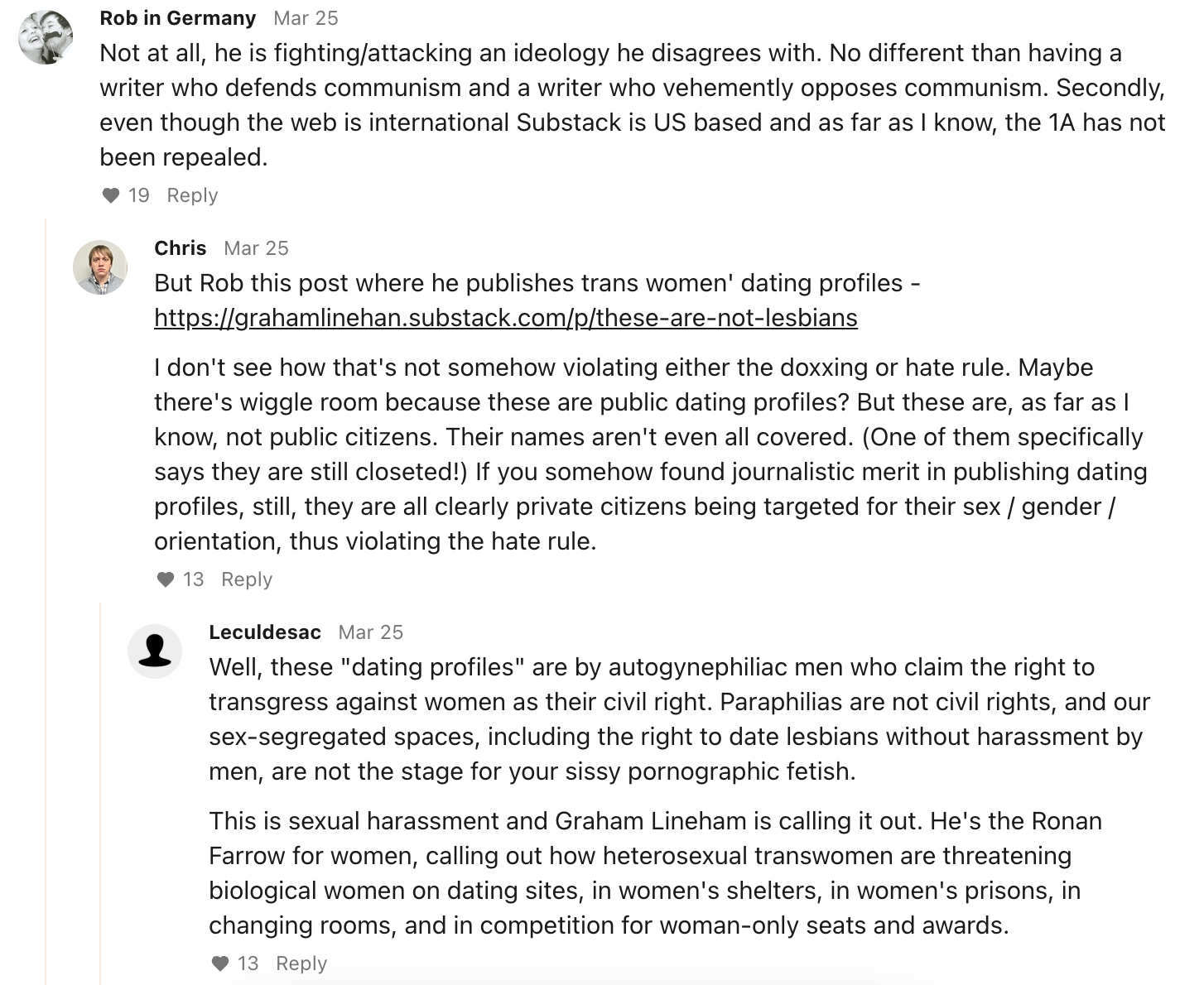

Since my last post, Substack has released yet another vaguely worded post about “putting writers and readers in charge” without giving into “public accusations or pressure campaigns.” On the surface, obviously, those are good values. But the post doesn’t engage with the actual issues at hand, leaving those who have followed the situation closely to understand that they are referring to hosting Graham Linehan’s newsletter while casual observers merely see an explanation of moderation guidelines. When the issue of Linehan came up in the comments of Substack’s post, his defenders jumped in to make arguments like the following:

(To address these shitty arguments: supporting the right of trans people to exist is not an “ideology.” The First Amendment does not prevent a private company from banning a user for violating its clearly stated content guidelines. Being trans is not a form of sexual harassment, a “pornographic fetish,” or a paraphilia. These are all extremely dangerous talking points targeting a very vulnerable population.)

My framework for analyzing situations like this is to analyze who benefits from upholding the company’s values and who gets harmed as collateral damage. In theory, Substack is promoting freedom of speech. In practice, a writer with thousands of readers is doxxing trans women with screenshots obtained by lurking on a dating app that they considered a safe space. Who benefits here? The cisgender white men who own the company, for one. It’s in their best interest to keep hosting Linehan’s newsletter and cashing in as it gains popularity among the vile people seen in the screenshot above. Substack will continue taking 10% of Linehan’s revenue, as is the standard rate, while its founders can feel brave for standing up to what Substack co-founder Chris Best referred to as “the thought police” in one subtweet.

And who gets harmed? One of the women doxxed in Linehan’s horrific post specifically states in her dating profile that she’s in the closet. These women could lose their jobs or their housing or their lives because of this. If Substack took this issue even the tiniest bit seriously, they’d at least ask Linehan to take this one post down. But even a slap on the wrist seems to be too much to ask of them.

I’m reminded, of course, of Twitter’s decision to ban Trump from its platform after years of racism, veiled threats of nuclear war, and dangerous dog whistles like “when the looting starts, the shooting starts.” Only when the Trump presidency was in its lame duck stage and when the public seemed to agree that Trump’s Twitter presence was linked to violence was it finally in the company’s best interest to apply their own rules. Before that, of course, Twitter benefitted from the massive engagement with the president’s deranged tweets. People of color were harmed as he emboldened overt racism from his supporters, but at least Jack Dorsey could claim that his company wasn’t biased.

I have only ever had one uncomplicated relationship with a website in my time on the internet (which, at this point, has spanned at least 20 years). I’m referring to The Toast, obviously, that beautiful safe haven founded by Nicole Cliffe and Daniel Lavery seemingly a lifetime ago. The site’s content was brilliant, of course, but The Toast also created a community. As Annalisa Quinn noted in a piece for NPR on the site’s shuttering, “The loving, supportive, collaborative nature of the comments section was such that one regular commenter gave another a kidney, and commenters helped another leave an emotionally abusive marriage.” None of that would be possible if it weren’t for the site’s strict comment moderation.

By aggressively moderating the comment section, the Toast team filtered out any form of harassment, even the insidious assholery. Anyone who’s been on the internet knows that the seemingly civil “just asking questions” comment is bullshit. (To quote Miles Klee for MEL, “By feigning curiosity and confusion, they smuggle in their bigoted views as the common sense of an ordinary, unblemished mind.”) There’s a lot of “just asking questions” right now from people who want to normalize bigotry and harm, and I wish we could call it what it is instead of pretending it’s all an intellectual debate.

I actually pitched some version of “The Worst Book I Ever Read” to The Toast shortly before they announced they were shuttering, so it was one of the first pieces I was excited to post to Friendmendations. Because of the self-indulgent nature of a self-run newsletter, I could write over 6,500 words on a book that was only 171 pages and hadn’t been relevant since I was a toddler, and it’s still one of my favorite things I’ve ever written. Building my newsletter here has allowed me to get paid for the hours I spend every week on silly nonsense like that — not very much money, but steady compensation that makes this feel like more than just a hobby and allows me to plan for future growth. It’s also allowed me to build a following. Again, it’s quite small compared to the many newsletters with thousands of subscribers. But my readers are so nice. I’ve heard from readers across the country (and across the ocean!) who have sent the kindest words of encouragement, appreciation, even condolences when my grandfather died. It means so much to me that people I don’t even know find value in the content I put on the internet.

But Substack isn’t the only platform. And it’s not a particularly attractive one right now. I’m so grateful to everyone who has written thoughtfully about their decision to leave Substack, including but not limited to Seth Simons, Dan O’Sullivan, and Emily Van Der Werff, because reading their insights has helped me solidify my own decision on this issue. With the size of my newsletter, I can’t quite tell if I’ll be making or losing money by switching to Ghost. But it would work out better for me financially if I grow this newsletter, and I want to.

This might feel a bit navel-gazey, and I promise I’ll go back to writing about Y2K or bad movies (or both) again soon. I have some new projects in the works, some clarity on what my job situation will be like in the future, and no plans to stop this newsletter. I appreciate you all so much.